If you have spent any time at all around hunting dogs—or any dogs, for that matter—one thing becomes immediately apparent: they live in a world that is vastly different from our own. The sights, the sounds, the touch, the taste of things may all be very similar to ours but, to a dog, a hunting dog in particular, it’s that sense of smell that changes their world into another sphere—one filled with a cacophony of aromas. Bird dogs learn to see with their noses. And their noses don’t lie. That’s one of the first lessons a new bird dog owner discovers: trust the dog. The dog knows things inherently that you and I can never comprehend.

If you have spent any time at all around hunting dogs—or any dogs, for that matter—one thing becomes immediately apparent: they live in a world that is vastly different from our own. The sights, the sounds, the touch, the taste of things may all be very similar to ours but, to a dog, a hunting dog in particular, it’s that sense of smell that changes their world into another sphere—one filled with a cacophony of aromas. Bird dogs learn to see with their noses. And their noses don’t lie. That’s one of the first lessons a new bird dog owner discovers: trust the dog. The dog knows things inherently that you and I can never comprehend.

Some of us try to force the issue, insisting that our dogs hunt in places that the dog already knows are devoid of game. We try to get them to “hunt dead” for a very live bird that the retriever, the setter, the pointer, the spaniel, knows full well is on the move and needs catching. We are limited, inferior predators. Yet our dogs love us anyway. That says much about the relationship that develops between human and canine.

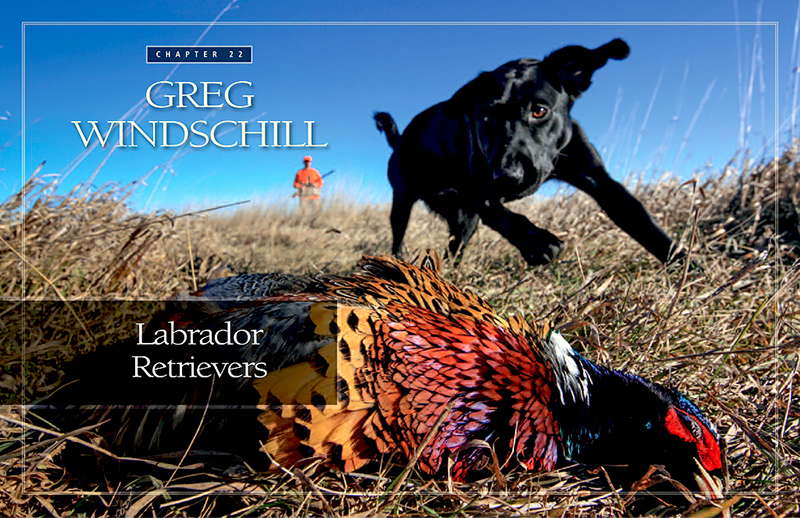

But there is a bird that is a great equalizer for man and dog, a noisy import that can give both fits. I am, of course, referring to the ring-necked pheasant. No other bird will try the patience of hunter and bird dog like a cackling, cowering, sprinting, spooky old rooster who has seen a hunting season or two and always seems to be two steps ahead of his pursuers. Because of their inclination to run rather than fly, ringnecks are the most difficult upland game bird for bird dogs to handle.

But there is a bird that is a great equalizer for man and dog, a noisy import that can give both fits. I am, of course, referring to the ring-necked pheasant. No other bird will try the patience of hunter and bird dog like a cackling, cowering, sprinting, spooky old rooster who has seen a hunting season or two and always seems to be two steps ahead of his pursuers. Because of their inclination to run rather than fly, ringnecks are the most difficult upland game bird for bird dogs to handle.

I would be remiss to not mention the absolute folly of owning bird dogs at all. The hurt we suffer when they go is sometimes unbearable, but we do it anyway. We bring them into our lives knowing full well that the joy will never last. No sensible person would undertake a project that involves so much blood, sweat and tears, with the knowledge that it’s all going to come crashing down in a few short years. Imagine building a house, and seeing to every detail, making it as perfect as you can, but knowing that that house will certainly, inexorably collapse in 12 or 14 years. No sane person would undertake such a project. Yet we do it all the time with our dogs. Such is the pull of bird dogs on hunters. As one of my friends will tell you later in this book, watching them go “is the price we pay.”

You should also know going in that Pheasant Dogs is definitely not meant to be a complete representation of all the breeds that serve as pheasant dogs. I learned early on that to try to cover every breed would be impossible. By my calculation there are at least 181 established hunting dog breeds in the world, and virtually all of them have been used for hunting pheasants at one time or another. Pheasants, after all, are the most adaptable game bird ever created. They exist on nearly every continent, so there are roosters being happily chased in strange places by breeds of canine that you and I will never know.

You should also know going in that Pheasant Dogs is definitely not meant to be a complete representation of all the breeds that serve as pheasant dogs. I learned early on that to try to cover every breed would be impossible. By my calculation there are at least 181 established hunting dog breeds in the world, and virtually all of them have been used for hunting pheasants at one time or another. Pheasants, after all, are the most adaptable game bird ever created. They exist on nearly every continent, so there are roosters being happily chased in strange places by breeds of canine that you and I will never know.

Even here in North America, there are breeds that you come across in the field only rarely, but their owners will gladly tell you about the prowess they show chasing wily ringnecks. I know of one person who hunts pheasants with a Doberman and another using an English bulldog. Traditional bird-hunting breeds those are not, but they still have that glorious gift of a nose. And that’s what matters, I suppose. A nose, and the ability to either pin a bird until the hunter arrives, or flush it in gun range, and then, in a perfect world, retrieve it—everything else, including athleticism, style and grace, is icing on the cake. Important icing, but icing nonetheless.

Of course, many flushing dog people would argue that it’s the latter point, the retrieve, that is essential in a pheasant dog. Rooster pheasants are incredibly tough birds. They can take a lot of shot and still land with their legs churning. They can cover ground like no other upland bird, sprinting with stealthy grit. This is where the rubber meets the road for a pheasant dog. It’s also where many hunters diverge in how they want their dogs to behave when the bird flushes.

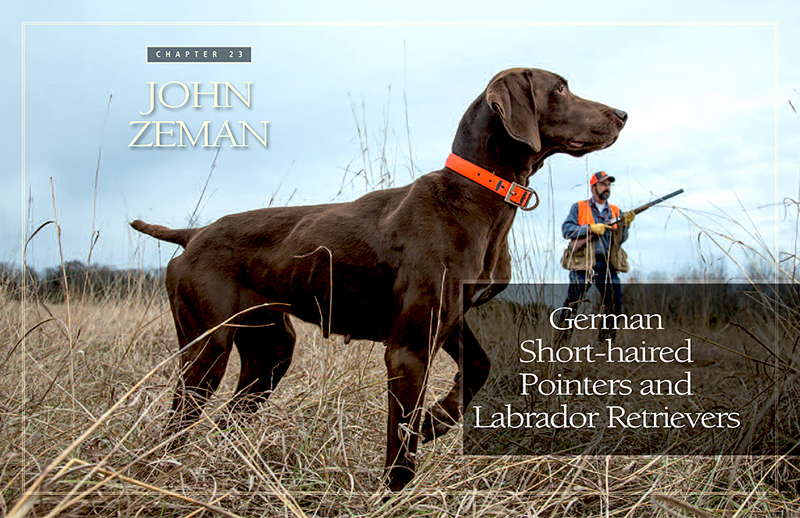

Purists and field trialers need a dog that is “steady to wing and shot.” For pointing breeds this means remaining locked on point, watching the bird fall if the hunter connects. For flushing breeds, being steady means the dog either sits at the flush or stands, marks and waits for the command to retrieve. Truly, it’s a thing of beauty to watch a dog so well trained that it remains stock-still when a cackling rooster vaults into the sky, inches from the dog’s nose. On the other hand. . . .

Purists and field trialers need a dog that is “steady to wing and shot.” For pointing breeds this means remaining locked on point, watching the bird fall if the hunter connects. For flushing breeds, being steady means the dog either sits at the flush or stands, marks and waits for the command to retrieve. Truly, it’s a thing of beauty to watch a dog so well trained that it remains stock-still when a cackling rooster vaults into the sky, inches from the dog’s nose. On the other hand. . . .

For some hunters, being steady to the shot is a luxury they don’t require or encourage. In fact, they want the dog in hot pursuit from the moment the bird flies. Giving a wounded ringneck a head start on the ground often results in a long, difficult search and retrieve for the dog—or perhaps even a lost bird. I must admit, I’m in the camp of those who want their dogs as close as possible to the bird when it hits the ground. But I certainly understand there are potential drawbacks to this as well.

Besides the fact that a dog ground-trailing a sprinting pheasant is liable to bump other birds during the pursuit, some dogs have trouble figuring out scent trails when the birds are plenty and they lose track of the wounded rooster. This phenomenon manifests itself regularly at the end of cornfield drives where scores of birds erupt en masses.

Regardless of how you prefer your pheasant dogs, the one thing almost everyone agrees on is: pheasant hunting is better with pheasant dogs.

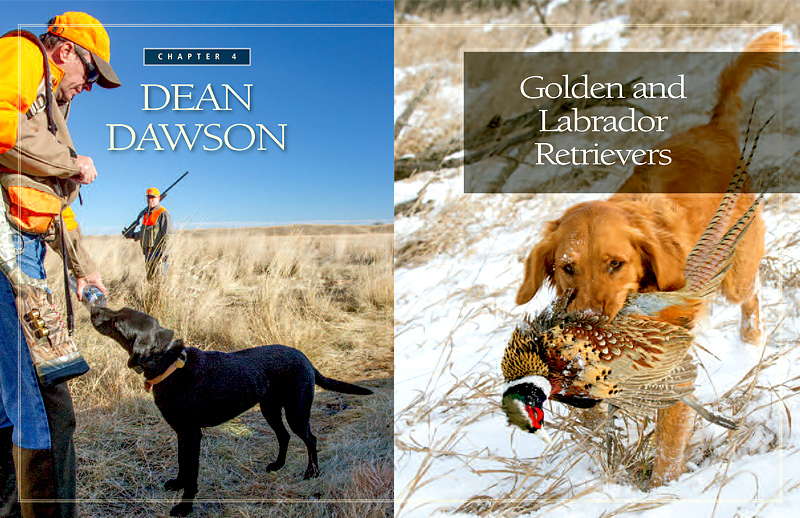

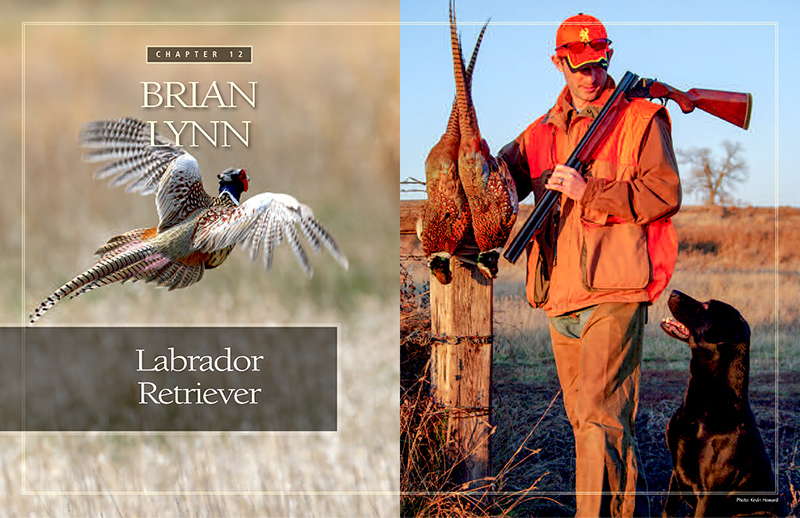

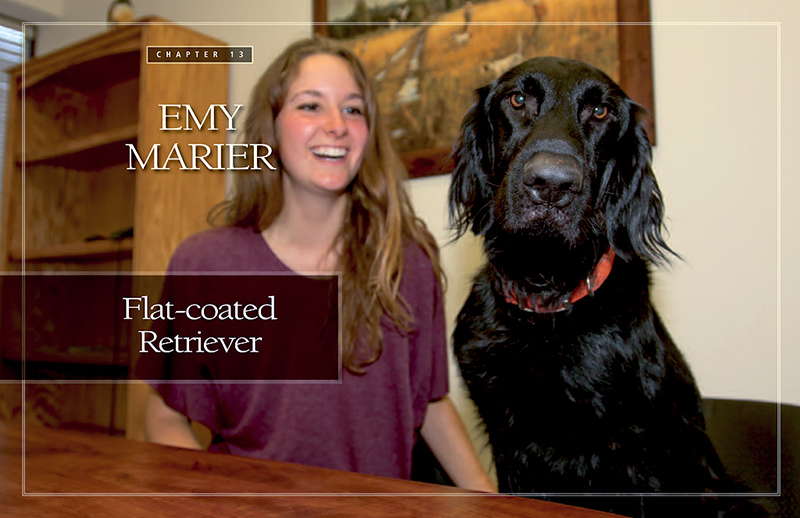

So, now we’re going to let you meet some pheasant-dog breeds and their owners. The only requirement I had for the interviewees was that they share my love of pheasant hunting and pheasant dogs—and that they had a story to tell. Some of those people are well-known in the world of hunting and hunting dogs; some you may never have heard of until now. Some are old pros. Some are just getting started. The best part about doing this book was meeting and getting to know people who are passionate and dedicated to pheasant hunting and to their chosen breed of dog.

So, now we’re going to let you meet some pheasant-dog breeds and their owners. The only requirement I had for the interviewees was that they share my love of pheasant hunting and pheasant dogs—and that they had a story to tell. Some of those people are well-known in the world of hunting and hunting dogs; some you may never have heard of until now. Some are old pros. Some are just getting started. The best part about doing this book was meeting and getting to know people who are passionate and dedicated to pheasant hunting and to their chosen breed of dog.

~From the Preface

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

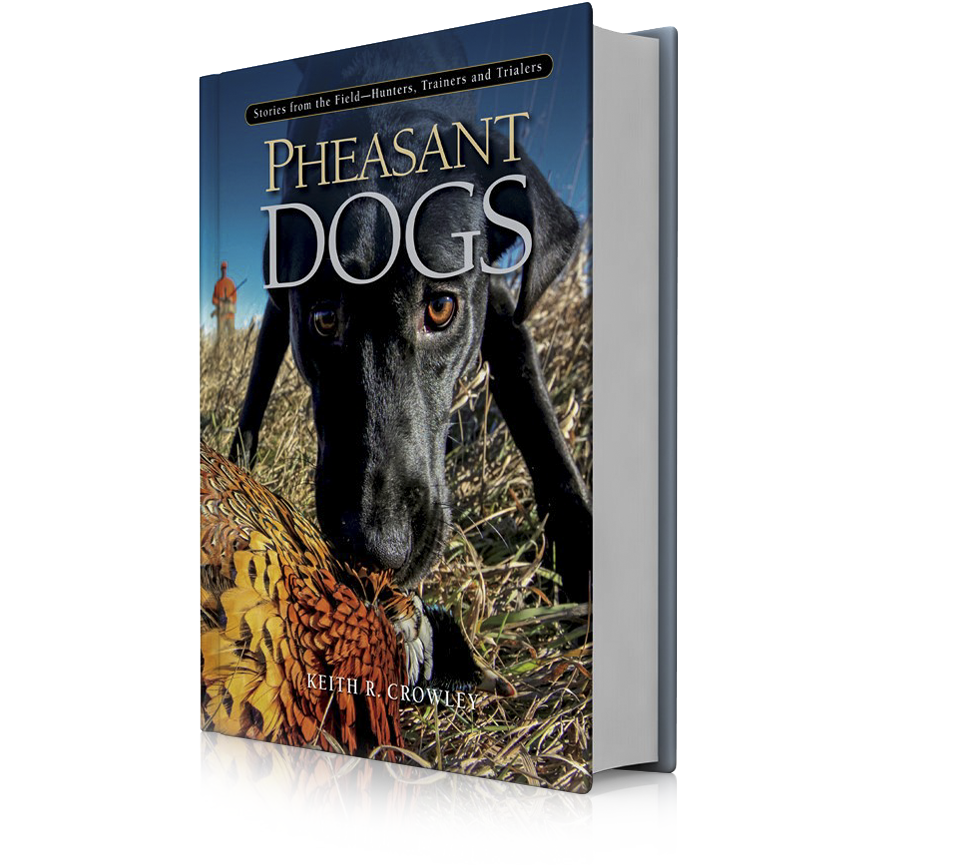

When Keith Crowley was a teenager, his first bird dog was an English springer named Briar. Today, decades later, Keith is a professional outdoor writer and photographer whose stunning images of wildlife from Africa to Alaska have won many awards. A lifelong pheasant hunter who makes his home in Wisconsin, Crowley spent six months from September 2017 through February 2018 traveling throughout the cornfields and hedge rows of the upper Midwest and Plains states, photographing bird dogs in action and listening to their owners tell stories. Some will make you laugh; some will make you cry. And you will learn a great deal. There has never before been such a vibrant, authentic, colorful book about field dogs. Pheasant Dogs sets a new standard—it will be immediately embraced as a classic by men and women everywhere who cherish the hunt and their beloved hunting dogs.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.